- Paranoia starts with a capital P and ends with a small a.

You have to open your mouth three times, first time beginning by a P to open for the a, second time being interrupted by the r to open for the a again, and the third time you will be interrupted by a no, or rather a nooi, to finally enchain with the last and longest, or most musical aaa – that a invites you to finish your word with an open mouth.

An open mouth is a sign of amazement, it can also be of trauma, of a scream (as famous as Munch’s scream), it can also be of sexual joy, or a mouth, while being electrified by a flogger who will enjoy spitting in it.

I have been asked to write three reports about my work “I Strongly Believe In Our right to be frivolous”. The last report -this one, shall stay online posted on KLF projects’ page, while the first two might not be directly visible.

While I write this report, I can’t stop myself from thinking out loud, asking myself such probable questions:

What is the difference between making an artwork, and writing about it? Between showing it in a space, hanging it with your fingers on an actual wall for instance, or posting it on Facebook, or on a virtual page, such as in this case, on KLF’s projects’ page, where we know that at any time, 24 hours a day, someone will be able to see it. Naturally, not see the actual work, but a few of its images, and also, read my three reports about it, and basically, seeing at first that last report, since the first two will not be directly visible.

When I return to a report or even a text about an artwork I have written a few weeks earlier, I often doubt its relevance and wish to change it. It would of course be too late. So I have learned not to read back what I have written about my artworks, to censure my doubts. But this does not seem right, what seems best to me is to “Let the works speak for themselves”. If the artist writes about his/her work, does that mean that the work is speaking for itself? It will be a ‘double trouble’, because it’s the artist trying to interpret her own work, by revealing a certain struggle, because she is revealing its process or itsmaking, like in films for instance and the moment during which it becomes ‘art’”.

Isn’t it that “in place of a hermeneutics, we need an erotics of art”? This is how Susanne Sontag’s famous essay of 1966 “Against Interpretation” ends.

I do believe that each artwork has a life, but that it also needs time to mature and to be looked at properly. An artwork needs this exchange with the people who view it in order to gain its independence and to reveal all its facets. Sometimes years later, if an artwork is shown, it gains other connotations.

But how does an artist, writing a report about his/her work, deal with this moment of publication online? And how do I deal with it with my particular work I Strongly Believe in Our Right to be Frivolous?

I found the third report the heaviest one to write unlike the first two which I managed to write with some lightness and without too much thinking. The third report is written here to prove that the work is almost coming to an end, which is hard for me. I struggle to see its end.

What I most enjoy while I work on I Strongly Believe in Our Right to be Frivolous is this very feeling of continuity, that this work might never finish.

In fact, I have encountered this feeling with each work I did so far, each time, imagining I would be doing what I am doing forever, seriously forever!

Since 2013, I have been meeting with displaced individuals as well as families. It all began when the Syrian revolution turned into a war and about a million and a half refugees came to Lebanon. From the onset, I was meeting with people as a way to welcome all those amazing new faces to Beirut, to counteract instances of racism, and help overcame the many difficulties they had to face upon arrival on Lebanese grounds– Lebanon being a destroyed place, unlike what people from Syria heard about it on TV before 2011, or imagined it before having to live there. Furthermore, the history between the two countries is very complicated. Syrians and Lebanese, while in the midst of the crisis, are still unable to look at things without prejudice. As disaster is followed by disaster, there is definitely no time to reflect; reflection is a luxury we might never afford.

From 2015, many of the Syrian friends that I had met in Lebanon were forced to escape to Europe, because from that year on, they had to arrange for sponsorships in order to be allowed to stay in Lebanon, on top of much costly paperwork. Plus, at a certain age, young men will be asked for the military service in Syria, so they find themselves too vulnerable to stay in Lebanon. From there, if anything goes wrong, they might end-up being sent back to the Syrian army or one of the fighting factions will take them. If they are illegal (even if they are legal), they might end-up being arrested to a Lebanese dark and racist jail. Hence, I followed in their footsteps and went to meet them there, in the camps were they were first received in various European countries.

At first, I wanted to check up on them and see if they were doing alright. I quickly and sadly realized that in the camps, they had to wait an absurd length of time before acquiring the status of refugee, knowing that most of them were not refugees in Lebanon, and would hate to be categorized as such. But once in Europe, they began to wish they would at least be recognized as refugees in the so-called “old continent”.

Little by little, upon visiting close friends in the camps and spending time in various places – starting north and moving southward until I had almost reached Beirut, (from Norway, to the Netherlands, Germany, Greece and Turkey) – I encountered refugees not only from Syria of course. Many came from Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Somalia, not to mention Iraq and Iran, and various other countries.

After visiting various camps and seeing how people got on with their lives beyond the camps, I sadly realized that each ethnic group sticks together, without mixing with others. Language and shared culture/history plays a major role of course, but there is more to it than that. The important thing is that I understood that while continuing my work from Europe, I ought to meet with people from various ethnic groups, since they are there and it would be a great opportunity to meet with them. I also thought I ought to foster encounters between them, to encourage mixing up together. Would I ever be able to do that? In Greece, I worked with an amazing association called Melissa, and it was particularly amazing because it refused to work only with Syrian refugees. The initiators of Melissa are six women from Athena, amongst them five are immigrants with residency permits, or even with papers in progress (even if they arrived from Philippine or Somalia or Ukraine since fifteen years for instance, to do the hardest jobs in Greece).

In Lebanon I was not only drawing refugees. The Syrian individuals I met, had various statuses: from doctors working at the American University (who of course need a permit to stay in Lebanon and have to go through the anxiety of renewing their permits every few months), to illegal political activists, to young people working in bars, art institutions or helping out refugees in camps and working hard to escape the label of refugee and to develop themselves in a difficult yet quite enriching place like Beirut – enriching because of the presence of mixed groups all struggling to survive, to be heard and recognized as well as a strong and active civil society, despite the non-functioning and highly corrupt parasite State.

However, I observed that the Syrians who were registered and recognized as refugees by the UN had no problem being called refugees. They usually wait for a phone call from the UN to be taken to Canada or a European country. The lucky ones among them have left by now. They prefer Canada to Europe, because they believe they get better chances there, and they get treated better. The Canadian officials expressed their solidarity with the Syrian refugees, since then, I have met a couple of people whom after being registered as refugees in Germany, tried to escape (in vain) to Canada from an airport in Norway for instance. From Beirut, The UNHCR, as I noticed, calls the most skilled among them and invites them to Canada, or to Germany, Sweden, anywhere. And they keep the rest waiting for years. Isn’t this an unfair manner to deal with millions of refugees? In some cases, how quickly you received that phone call depended on your ethnic background.

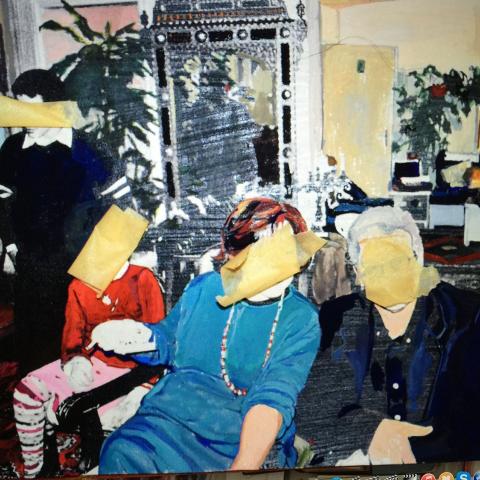

Whether in Beirut or Europe, whenever I meet someone, we would habitually sit together and I would proceed to take notes of our conversation. I would also sketch a portrait of that person. This might include details such as their hands, a detail from something they are talking about, things they believe in or even things they ask me to draw next to their portraits.

Our encounters are like recorded conversations. Each conversation allows for a back and forth and an understanding. If someone doesn't understand what the other has said, she/he can ask: What did you say? Or what did you mean? I think this is an important aspect of the work.

I write and draw our encounters on a yellow notebook. I chose the yellow notepad simply because it's the one you find in all the offices and bookshops in Lebanon; it’s the notepad I have always used when meeting people for interviews, or whenever I was undertaking research for my work. I like it because you flip the page as you go, and it allows for a good flow. I like that it isn’t white (so I am not facing a typical white page or a white canvas), nor blue nor pink, (like for instance the Turkish identity card, blue for men and pink for girls), and it allows working with drawing and writing because it has lines. It is also one of the few relatively good quality notebooks in Lebanon that are made locally.

So this yellow paper became like the skin of this work, I take it with me wherever I go. If I ever forget it, I exceptionally use another notebook, or some found papers. In Athens for instance, I had to use another one, because I had forgotten mine, so I found a local notebook, similar to mine, but it was a white one with gray stripes on the page.

As for the embroideries, I had worked out some portraits, drawing their “essence” onto beige textile, and embroidering them, with the help of some refugee women (more details about this can be found in the previous report). At this stage I realized, that the embroidering I am making is very personal, and I might therefore continue working on my own, to complete all the embroideries, hoping they will be shown in Athens next year.

Now, hold on, do I have any idea about how to end this report?

If the artist writes about her work, does that mean that the work is speaking for itself? But here, I assume once more, that the idea is that each artist would ‘pretend’ to take a step out of the work and write about it, almost as an outsider, as a new spectator.

“- Hello, this is not me who made the artwork; therefore, I am able to write about it in a dry manner.” Artist.

Or perhaps, I can say, I am writing a report, spying about myself. And then instead of, for instance, handing it to the regime, or to a dictator, or rather to the guards of that dictator, or perhaps to an ISIS Amir, I post it online. The dictator or the Amir, and their guards are free to see it or not to see it. The dictator is too busy to read this anyway. But the option is there. How about al Qaeda in Afghanistan?

The dictator here can be anyone and is everywhere in fact, and if you start a paranoia trip, you will notice there are no limits, since we live in the internet time, and in the Facebook pages– especially those who come from calamity zones rely increasingly on Facebook, and live fully immersed in it.

These days I wonder, do we meet people , in order to add them as Facebook friends? Do we write posts to reveal what we are thinking, or to ‘show’ that we are thinking, or feeling? That’s another topic marking the end of this report thankfully.

About the artist

Mounira Al Solh's visual practice embraces video, painting, embroidery and performance. Integration of social and political themes grounded in daily life are reflected in research, as well as in production and presentation of work and in the role of the investigative organizer Mounira has. Al Solh's art aspires to ask large questions in small places, operating according to Ginzburg's notion of microhistory. Humor is surprisingly an integral part of the artist's work, concealing trauma in laughter as a way to process it.

As the editor of NOA (Not Only Arabic) magazine, a performative gesture co-edited with collaborators such as Jacques Aswad and Mona Abu Rayyan, and of NOA language school (with Angela Serino), Al Solh examines topics such as treason, arrest, fragmentation of language and schizophrenia in dialogue with artists and writers.

Her work has been displayed in exhibitions at the Venice Biennale, Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Beirut; Kunsthalle Lisbon, Portugal; Art in General, New York; Lebanese Pavilion at the Venice Biennial; Homeworks, Beirut; The New Museum, New York; Haus Der Kunst, Munich; Manifesta 8, Murcia, Spain; The Guild Art Gallery, Mumbai; Stedelijk Museum Bureau Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Al Riwaq Art Space, Manama, Bahrain; Kunst-Werke Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin and the 11th International Istanbul Biennial.

In 2003 she was awarded the Kentertainment Painting Prize in Lebanon and her video Rawane's Song received the 2007 jury prize at VideoBrasil. She is Uriot Prize winner at the Rijksakademie, and was nominated for the Volkskrant Award in the Netherlands in 2009. Most recently she has been shortlisted for the Abraaj Group Art Prize, 2015.

Mounira Al Solh studied painting at the Lebanese University in Beirut (LB), and Fine Arts at the Gerrit Rietveld Academy in Amsterdam (NL), where she was also research resident at the Rijksakademie in 2007 and 2008.

Al Solh teaches as a guest in various art schools in the Netherlands and in Beirut, and she is represented by Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Beirut & Hamburg. She lives and works between Amsterdam and Beirut.