The project Learning Not to Dream was finalised in early 2015 with the completion of a dual-subtitled (Arabic/English) digitised edition of Kassem Hawal's 1982 documentary Massacre: Sabra and Shatila. An essay exploring the 35-minute film's form and history is being developed for journal publication at a later date in 2015. This expands on themes raised in these project updates. Exhibition of the film is being planned to coincide with the 2015 commemoration of the massacre at Sabra and Shatila in September.

Previous updates combined reflective notes on the film's form with the director's recollections of its making and an account of his cultural and political work during the years surrounding the film. The previous update focused on Massacre's initial 20-minutes, in which survivors of Sabra and Shatila recount atrocities they witnessed and experienced. This final update treats the film's closing chapter, in which it undergoes a tonal shift as testimonies of a different nature are introduced which point toward a cluster of subplots and parallel histories beyond the film itself.

Captive testimony

"They took me in a car over a very long distance in Syria, through the desert. To a place where there were just a few small trees. And there, they opened a door, like a big iron thing in the earth. They opened it, and we went down many steps, along really narrow passages, until I entered a large space with many rooms: salons, a clinic, and lots of other rooms – deep in the ground. And there were the Israelis."

— Kassem Hawal, correspondence, October 2014

Twelve minutes of interviews with POWs in a hidden facility below the Syrian desert makes for disconcerting viewing. How does this abrupt descent into a new (sub)terrain of largely choreographed 'confessions' effect Massacre's visceral anterior of spontaneous witnessing from camp survivors? And what are the ramifications of making these scenes visible again?

Because it is here, in an underground complex run by the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, General Command (PFLP-GC), that Massacre arrives at its prosecutorial summit. It does so though interviews with two captive Israeli infantry soldiers: Yosef ('Yoski') Groff and Nissim Shalem. Both give cognate accounts of their capture and fine treatment by the PFLP-GC, before issuing carefully worded judgements on the horrors at Sabra and Shatila that assign responsibility to the Israeli army and regime.

The PLFP-GC, under its erstwhile founder-leader Ahmed Jibril, remains a militant, if increasingly marginalised and discredited force. As such, is Hawal concerned that, seen today, these scenes may attract unwanted scrutiny or even charges of direct involvement in the group's past operations?

"No, no – no problem. It's very clear, the interview with them, and how I met them there."

— Kassem Hawal, correspondence, June 2014

The POWs show no sign of ill-treatment, and Hawal recalls leaving the facility sure they were being well cared for. But it is not self-evident from the film how the encounter came about. Hawal had no part in their capture or imprisonment and was not affiliated with the PFLP-GC. His access resulted of a chance personal association with the relative of a PFLP-GC intelligence officer. He was conveyed to and from the facility blindfolded, and was confined to an hour's contact with each prisoner, under close supervision.

Groff and Shalem appear separately, each ostensibly in their quarters, which are decorated (in anticipation of the filming, one assumes) with flags, posters, and other bearers of the PFLP-GC insignia. Of the two, Groff is most assured, speaking confidently in deliberate English. Shalem is perhaps less at ease. He speaks in a Hebrew evincing odd grammatical slips that may belie a note of anxiety as well as a subtle 'levelling' to the imperfect Hebrew of his unseen interlocutor.

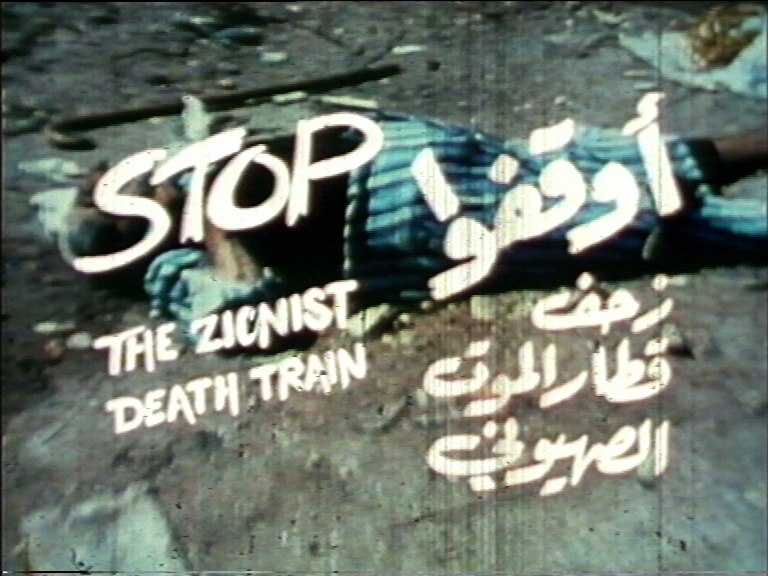

Excerpt, Massacre: Sabra and Shatila, 1982, Kassem Hawal. Courtesy of the artist. Excerpt from Arabic subtitled digital scan from analogue Umatic tape, 2014.

At points the rehearsed quality of the exchanges tilts toward comedy. Groff, listing the PFLP-GC's efforts to afford his observance of Jewish rites and holidays, holds up evidence in the form of an English language edition of the (Christian evangelical) Good News Bible. When Shalem is asked "Since you were taken, how have you been treated by the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, General Command…", he interjects himself to complete this dutifully memorised full-form Hebrew iteration of the group's identity: "... under the leadership of Ahmed Jibril?" – only then proceeding to address the question.

Excerpt, Massacre: Sabra and Shatila, 1982, Kassem Hawal. Courtesy of the artist. Excerpt from Arabic subtitled digital scan from analogue Umatic tape, 2014.

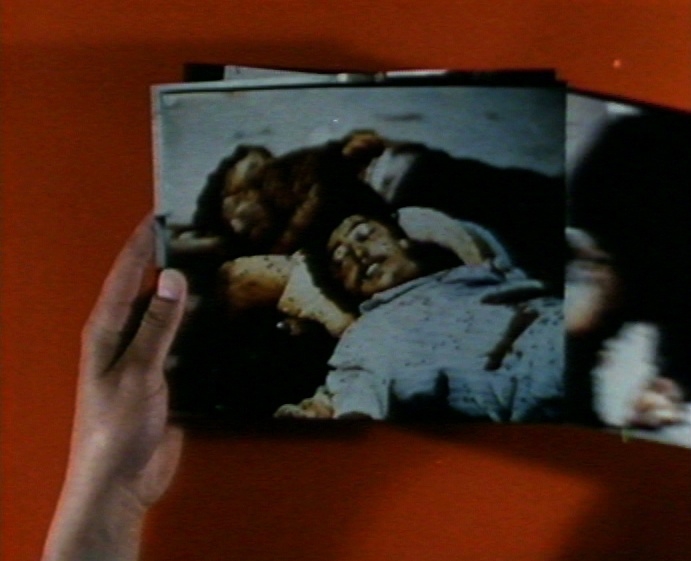

Not every passage was so rehearsed prior to the film crew's arrival. Without notifying the PFLP-GC, Hawal brought along a set of photographs taken in the aftermath of the massacre. Groff's reaction does seem one of genuine distress as he confronts this visual evidence. It is soon after this, the most affective passage Hawal obtains with the POWs, that both are seen delivering their verdict on Israel's responsibility.

"They were dreaming, not fighting"

Yosef Groff and Nissim Shalem were captured in June 1982. With another PFLP-GC prisoner, Hezi Shai, they would remain in captivity until May 1985, when they were released in the so-called "Jibril Deal". This saw the three soldiers swapped for 1,197 Israeli-held captives, including Ahmad Yassin (later Hamas spiritual leader Sheikh Yassin) and the Japanese Red Army's Kozo Okamoto (of the 1972 Lydd Airport attack).

Hezi Shai, a tank sergeant captured in battle, was feted on his return to Israel. But Groff and Shalem, captured whilst napping beneath a tree in southern Lebanon, were not. Israeli parliamentarians called for them to be tried for cowardice: "they were dreaming, not fighting"; the military found their conduct "below standard", assuring the public "appropriate conclusions had been reached".[1] Both men withdrew from the public eye whilst Shai became a source of national pride, giving motivational talks to soldiers and becoming a familiar media figure in connection with campaigns for Israeli POW's or MIA soldiers.

Over 2009-10, the "Jibril Deal", and the figures of Groff, Shalem, and Shai were catapulted back to the fore of Israeli public discourse. The "high price" paid for the three back in 1985 was being cited as an egregious error and even a national disgrace as efforts were made to limit the scope of any forthcoming swap for the Hamas-held Gilad Shalit. In 2009, Gideon Raff began shooting a TV series about Israeli POWs brainwashed and recruited by their captors. Hezi Shai was consulted during the making of Prisoners of War, later rebooted in the US as Homeland.[2] With its broadcast in early 2010, memories of the 1985 "Jibril Deal" and the seemingly imminent "Shalit Deal" grew further entangled. Yosef Groff's mother Miriam now condemned Prisoners of War as "a promo for Hamas and a Shalit Deal … it will only encourage more kidnapping of soldiers".[3]

Then, in March 2010, Aljazeera aired 4 minutes of previously-unseen footage of Groff and Shalem in captivity in 1983 (shot by an unidentified crew). Extensively re-aired on Israeli TV and web platforms, the clip saw both denouncing Israel's military and settlement policies.[4] A quarter of a century after their release, the nationalist outcry this sparked forced Groff and Shalem to make statements dissociating themselves from material they insisted was filmed under severe duress. This was an eventuality that had actually been anticipated back in 1982, as the final interview sequences containedin Massacre demonstrate:

Excerpt, Massacre: Sabra and Shatila, 1982, Kassem Hawal. Courtesy of the artist. Excerpt from Arabic subtitled digital scan from analogue Umatic tape, 2014.

45 Minutes in Beirut

The denigration of Groff and Shalem as "dreamers" rather than "fighters" points to values and anxieties pervading a mobilised nationalist society. Associated with capture in dereliction and cowardice, their conduct as POWs was later linked with frailty and betrayal. Interpolated through an echo-chamber of political and fictional dramas, a Groff-Shalem construct emerges, steeped in the anxieties of militarised nationalism: the dis-armed (and disarming) antitype to that indestructible soldierly ideal about which the nation in arms continues to compose its core aesthetic and ethical universe.

It's not obvious what all this spells for the current project. The events of 2010 confirm that the Israeli media and wider public, if not the security services, are as yet unaware of Massacre's longer and potentially more incendiary 1982 interviews with Groff and Shalem; and that the material may well spark a backlash of some sort. However, with the "Shalit Deal" context and the uproar over the footage aired in 2010 both now faded, perhaps this quiet return of a Zionist anti-hero will pass unnoticed. As we discuss these concerns over some months, Hawal remains adamant:

"No, no. You can watch it, you can print it, you can show it, you can send it to people. I told you: this is a historical period for me. It's also a great story."

— Kassem Hawal, correspondence, November 2014

It was a historical period often fraught with risk. Hawal had evaded an assassination attempt by Iraqi agents in Beirut three years before making Massacre. Another attempt followed after he had moved to Greece in 1984 – both resulting of his work coordinating Iraqi dissident writers and artists in exile. And part of the "great story" Hawal recalls in relation to Massacre involves another close call: a near-calamitous blunder made as he left Damascus for Athens with the footage he'd shot of Groff and Shalem in the PFLP-GC facility:

"It was a very sensitive situation because the Israelis were really trying hard to find out were these people were being held… Now, at that time I was trying to take direct flights, so direct from Syria to Greece of course. But just as I was on the plane, I found that the flight I was on was going to be stopping in Beirut! I couldn't turn back because my baggage was already inside, and the film was with me, and I was already late because of issues getting the film through the airport. They'd only actually let me on the plane at the very last minute, which is when I found that the plane was going via Beirut – at that time, the Israeli occupied airport…

"The plane landed in Beirut, and the Israelis came to the plane. And the films were with me! It was a very dangerous moment. You can't imagine what I was feeling… The plane stood there for about 45 minutes. It was an unbelievable wait… And there were some Phalangists getting on the plane in Beirut as well; journalists, and they knew me…

"After 45 minutes, the plane flew on to Greece. I immediately asked for a bottle of wine!"

— Kassem Hawal, correspondence, October 2014

The editing and post-production of Massacre was completed in Athens by the end of 1982. The film was screened in Damascus in 1983, and the Libyan government, which had demanded a prominent production credit, broadcast the film the same year; but Hawal never received the funds he'd been promised. Initially from in Syria, and then from Greece, Hawal then returned to a project begun before the massacre. This documentary, responding to Israel's plundering and vandalism of Palestinian cultural and social infrastructures in Lebanon, was completed in 1984 as The Palestinian Identity.

As the Massacre project draws to a close, Hawal returns to a central motif from our first discussions of his experiences in the arts amidst the optimistic heyday of the Palestinian Revolution in the mid-1970s: That of a cherished, if painful chapter that is now firmly closed; an era of inspiring but unrealised dreams that was ended in agonising nightmares. He turns again to those anxious 45-minutes on the tarmac at Beirut airport:

"At the time, this was my character in a way – I didn't care about risks so much. That's why I'm telling you: this was a period in my history, and it's finished."

— Kassem Hawal, correspondence, November 2014

Conclusion

The highly-distinct and initially disconcerting field of POW testimony contained in the final scenes of Massacre might be seen as jeopardising the integrity and persuasive force accumulated in the film's preceding body of survivor witnessing from the camp. But it might also be read as integral to the quite specific aesthetic and political bearing of both the film and its director.

Taken as a whole, Massacre is a singularly potent work of anti-Zionist cinema because it is guided not by the simple parameters of national liberation, but by a more radical internationalist humanism; one in which the savage effects but also the agents and workings of militarised colonial violence are rendered visible and unsettled. Massacre's distinct fields of testimonies and visibilities share a common feature under the logic of Zionism the film works against. Both map inadmissible bodies of evidence; disruptive, and thus eradicated narratives and lives: the unarmed Palestinian civilian, and the dis-armed Jewish Israeli soldier.

Accessed February 2015.

Accessed February 2015.

http://www.ynetnews.com/articles/0,7340,L-3861583,00.html

Accessed February 2015.

About the artist

The Palestine Film Foundation (PFF) is a London-based research and exhibition structure specialising in film and video work from and upon Palestine. Founded in 2004, the PFF manages a range of film preservation, subtitling, education, and programming activities in the UK, including the annual London Palestine Film Festival.

This project will be conducted by the PFF's co-director, Nick Denes, who leads the PFF's research and preservation programme. Denes is a film curator and sociologist. He is Senior Teaching Fellow in the Centre for Media and Film Studies, SOAS, University of London, and has published widely on moving images of and from Palestine, the 'new far right' in the contemporary EU, and surveillance in Palestine/Israel.