Under-Writing Beirut – Nahr (the Arabic word for river)[1] investigates the urban areas adjacent to Beirut's river particularly the area named Jisr el Wati (the low bridge in English) [2]. In this project I look back, from the present, at the sociological, political and economic history of this area in order to understand and produce narratives that are meaningful today and insightful into the past. What kind of narratives can emerge from and be triggered by such places, rather than represent them? It is a question I have raised in my feature film And the living is easy (2014). How has political decision-making or lack thereof transformed the area and how does it translate into its everyday life, making this area the space where Lebanon's most crucial problems converge? How does such a place affect and inform the production of art?

My initial involvement in this landscape started in 2004 when searching for a space to establish Beirut Art Center (BAC),[3] which I co-founded with Sandra Dagher, and which opened in this area in January 2009. Our final choice of this area was led by both the necessity to find a large space and the financial restrictions related to the project. Indeed, the place was mostly filled with factories and warehouses, originally built in the 40's, 50's and 60's.Today the neighborhood is a largely diversified area on the edge of Beirut city, both in terms of its populace and their economic activities. Such diversification spans many nationalities and ethnic groups of refugees and migrant workers. Economically, the diversification reflects the activities of the populace ranging from craftsmen, art practitioners, and prostitutes to construction workers, architects, engineers and real estate development companies. Although administratively part of Ashrafieh in Beirut, the place is perceived as the periphery of the city.

The recent and rapid transformation of this area invites a reflection on several intertwined aspects that engage the river and its surroundings. The first one revolves around the location of Nahr Beirut in relation to the city and engages with the idea of 'borderscape'[4]. While defining the eastern edge of the city, the river acts both as a connector and a separator between Beirut and its suburbs.[5] The second aspect takes up the diverse migrant population that has historically been located at the periphery of the city, absorbing the surplus of incomers to the urban center, which led to the creation of settlements by the river, and constituted later what was named the "belt of misery."[6] One last aspect involves the potential for gentrification of this area, one of the few remaining underexploited spaces in the capital, starting with the fast development of what has been a non-residential neighborhood of poor and derelict character as it is manifested in its rundown factories, train station, as well as in illegal practices such as prostitution and criminality, into a place of interest for art practitioners and soon a high rise residential area.

"Nearer to the coast, again to the east, overlooking the modern port and bordered by a river that bears the city's name, Nahr Beirut (known to the ancient Romans as Magoras), the hill of Ashrafiyeh rises to a height of more than three hundred feet."[7]

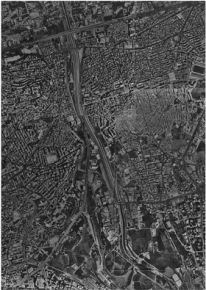

Nahr Beirut defines the eastern border of Beirut since the official decree of 1956.[8] It springs from the Western slopes of Mount Lebanon and runs westwards then northwards separating Beirut from its eastern suburbs. It flows into Beirut's northern Mediterranean coast, to the east of the port. The Romans had built a dam to diverge the water under the Daychounieh source to convey water to the city through the aqueduct of Zubayda. The system supplied water to the city until it fell in ruins during early Ottoman times. Since then, Nahr Beirut contributes only partially to irrigating the city. Later, under the French mandate, a concrete division dam was built (1934) to irrigate agricultural lands around the river.[9] The built infrastructure only lasted a year. The canalization of Nahr Beirut from the waterfront to Sin El Fil was achieved in 1968. It was triggered by the damaging Nahr Beirut flood of 1942 which resulted from the migrants' gradual and informal urbanisation and encroachment on the river flood zone[10] but also and especially by the 100 years flood of Nahr Abou Ali in the Northern city of Tripoli in 1955, which claimed human lives and destroyed thousands of houses and agrarian lands.[11] Interrupted by the civil war, the canalization of the area between Sin el Fil and Jisr el Basha was only completed in 1998. There are currently six bridges that connect Beirut to its suburbs across the river which were built in the period 1940s-1970s: the Dora bridge, the Borj Hammoud bridge (on the old remnants of the Ottoman bridge), Jisr el Wati at Sin el Fil, and Jisr el Basha situated meters away from the Ottoman bridge remains.[12] The bridge right by Beirut Art Center is Jisr el Wati, mentioned earlier, which is now rapidly transforming.

"A finer situation cannot be imagined; it is a green sod, and ends on the east side with a hanging ground over a beautiful valley, through which the river Bayreut runs; the north end commands a view of the sea, and a prospect of the fine gardens of Bayreut to the north-west. […]I set forward on my journey from Bayreut on the first of June, and went to the east along the side of the bay; after having travelled about a league, we came to the place where they say St. George killed the dragon[13] which was about to devour the king of Bayreut's daughter: there is a mosque on the spot, which was formerly a Greek church; near it as well, and they say, that the dragon usually came out of the hole, which is now the mouth of it. The writers of the middle age say this place was called Cappadocia. […] About a mile to the East of this place we crossed over the river of Bayreut, on a bridge of seven arches, some of which are of ancient workmanship. This river runs to the north along the plain, which is east of the grove of pines; it may be river Magoras, of Pliny, and agrees with his order in speaking of places; though some think it is the same as the Tamyras."[14]

Until 1850, the Nahr had been an agricultural plain. Accounts by inhabitants describe the areas around the river in the first half of the twentieth century as abounding with "nature": banana trees, orange and lemon trees, tomatoes, and gardens. Back then, the river was used by its residents for domestic and daily activities: mothers used to do laundry in the river on Saturdays and use the river water for cooking, children used to bathe there too and some would even fish in it or play at catching frogs and snakes. People regularly crossed the river to visit their relatives living across or to shop in specialized markets in Achrafieh or Sin el Fil. In other cases, the river was a safety valve separating rival Armenian political communities from each other who even turned the bridge dating from the French mandate into a battlefield at some point in time.[15]

The development of the port as a major asset for the capital city's rise in the nineteenth century propagated the infrastructural development of the areas extending behind the port.[16] In 1834, the lazaretto was built as part of the port development and as a result of the Egyptian concern for public hygiene in confining epidemics. It was chosen to "lay outside the city, but not too far" in the area which kept the name, Quarantina, until today.[17] The establishment of the quarantine further promoted the economic development of Beirut by upgrading and expanding the harbor to an international port of call.[18] Starting in the 1920s the Nahr got populated and urbanized at a rapid pace.[19] Because of its location, Nahr Beirut developed into a major infrastructural hub connecting the port to the hinterlands.[20] Specifically, warehouses and shipping services developed in the waterfront zone of the river. Indeed, increase in maritime commercial traffic led to the development of warehouses for storage and recycling of bulky merchandise. All in all, it was a "hasty and unplanned urban development" which resulted in a display of symptoms of blight and degeneration in the port region.[21]

"All description of Beirut prior to the 1860's attests to this. Until then, it was no more than a small fortified medieval town with seven main gates and about one quarter of a square mile surrounded by gardens. The central core of the city was built around its historic port and mole with defenses on the landward side and two towers at the entrance of the port. As in most European towns before industrialization, people in Beirut lived and worked within the same area and carried on nearly all their daily routines within the same urban quarter."[22].

Around the same time, a wave of migrants established their home around Beirut's river. In World War One after the Genocide of the Armenians by the Turks, tens of thousands fled their home and settled in a camp in Quarantina and most later moved to Borj Hammoud. Syriac communities arrived in this area following deportation campaigns by the Ottoman Empire in the early 1920s.[23] Several waves of incoming Kurds fleeing the Turkification policy under Mustafa Kemal Ataturk and its associated violence also settled in the Quarantina. In 1948, an influx of Palestinian refugees settled in these camps and others around the city. Reports on slums often mention Arab workers – especially Syrian – in the slums prior to the war.[24] Demographic pressures on the periphery of Beirut manifested in poorly constructed and nondescript buildings: "[i]mmigrants crowded together instead in old, hastily adapted rural cottages or in new concrete structures, ill-equipped and devoid of elegance, along mostly unpaved roads."[25] The shortage of municipal and public services in the periphery of Beirut facilitated the emergence of poverty and disease.

"Not only was the spread of urbanization the result of a lack of systematic planning; it occurred at a pace that outstripped the city's ability to provide basic services, with the result that Beirut could not rapidly assimilate so many newcomers without itself being deformed."[26]

The economic boom in the late 1940s triggered the growth of the industry sector along the river.[27] Furthermore, the building boom of the 1950s-60s and the pressure from private developers contributed to the unregulated patterns of growth around the river. The ring of slums abruptly grew in 1965-1970 extending from Quarantina/Nahr Beirut to the edge of the airport.[28] Indeed the growing industrial sector of the 1960s was attracted by the cheap labor and located its new factories around slums inhabited by rural migrants, migrant workers and refugees, revealing the other side of this "growing affluence."[29] "Slum dwellers and industrial developments fed on each other."[30] In the 1970s, Beirut was already experiencing "over-urbanisation" as the degree of urbanisation was beyond what would be expected from the level of industrialization.[31]

"Suffice it to note that this is one of the most critical problems Lebanon continues to face, a problem with serious social, psychological, economic, and political implications. Urban congestion, blight, depletion of open spaces, disparities in income distribution, rising levels of unemployment and underemployment, housing shortages, exorbitant rents, problems generated by slums and shantytowns, and, to a considerable extent, the urban violence of the war years were all by-products of over-urbanisation. In short, the scale and scope of urbanisation had outstripped the city's resources to cope effectively with continuously mounting demand for urban space and public amenities."[32]

At the edge of the city, Nahr Beirut acted both as the "natural" boundary of the growing capital city and as a shifting area hosting a diversity of refugees over time. Today there are little noticeable traces of the war in the area. During the Lebanese war this area, as part of eastern Beirut, was under the control of Christian Militias and was the site of a few bloody battles. In 1975-76, early rounds of fighting started in the city center and extended outwards to the hotel districts and the south-eastern suburbs creating the "Green Line" dividing Beirut into two (Muslim West Beirut and Christian East Beirut). This affected the social geography of Beirut in creating "exclusive and closed communities."[33] Entire groups were evicted from the western and eastern zones of the city depending on their religion and they moved collectively towards safer areas.[34] Indeed, Muslim enclaves in East Beirut (Quarantina, Nabaa, Tal el Zaatar) were destroyed.[35] Much of the urbanisation of the city's peripheries activated by the fleeing populations happened illegally in violation of construction codes and property rights regulations.[36]

In 1985 other battles involving rivalry within the Lebanese Forces occurred in the area.[37] Later shootings between the Lebanese army under the command of army commander Michel Aoun and the Lebanese Forces divided and affected the eastern area of Beirut and its suburbs.[38] In one instance, accusations by the Lebanese Forces claimed that the army shelled Jisr el Wati that connects Sin el Fil to Ashrafieh to cut them off from supplies.[39]

Today, the eastern suburbs witness an ageing and informal urbanisation with abandoned factories and cheap and unhealthy living quarters. In addition to the older waves of migrants who settled around the river, the eastern suburbs host immigrants from East and West Africa as well as from Asia (Filipinos, Indians, Sri Lankans, Bangladeshi and Nepalis).[40] A large number of non-Lebanese workers moved to the suburbs in the 1990s, notably among them Syrian male workers.[41] Recently, the tragic situation in Syria triggered new waves of unfortunate Syrian refugees among which a large population is actively participating as labor force in the construction sector including projects in the Nahr/Jisr el Wati area. Syrian migrant workers have historically provided the labor force for the construction industry taking up hard work with mediocre pay.

Two important public and popular markets, Souq el Ahad which opens every Saturday and Sunday where lower-income and migrant workers can find inexpensive products such as clothes, shoes, fabrics, cosmetics and general domestic items, and the vegetable market, Souq el Khodra, were created. They are both located around Jisr el Wati, right by the river. The neighborhood is also characterized by highways along the riverbanks almost drowning the dry river under the eyes of the passersby and the drivers. Mostly inhabited during the day and buzzing with construction noises and fast cars, the area drowns in hollowness and dark spaces at nightfall. Sights and stories of sex workers and criminal incidents convey the derelict attribute of this place.

The river has for a long time been abandoned as a site of dumping not only by passers-by but also by the surrounding factories dumping all sorts of dyes and polluted material, by Souq el Ahad and Souq el Khodra, the slaughterhouse also had its share of dumping some remains in the channels, and the government as some of the sanitary sewage systems end in the river. Nahr Beirut made it to the headlines when it "mysteriously ran blood red"[42] because of red dye discharged by a factory along its banks. First fears and speculations were that the red-colored river had blood running through it but tests on the water showed that this is only one of the many times the river has changed colors because of the draining of all sorts of pollutants and sewage into it. Cattle herds, as well as some wild animals such as crocodiles and an endangered species turtle were also spotted along the river. While pictures and television footage of a "lurking crocodile"[43] scared people and sparked their imagination, the story turned out to be that the crocodile was abandoned by his owner in the river.

The overall neglect contributes to the flooding of the river in the winter and its drying out in the summer with all sorts of repugnant and toxic odors, and the sprawling of rodents and insects. Furthermore, the current canalization of the river cannot contain the maximum flood limit of Nahr Beirut. The canalization of the river, which was completed in 1998 could not prevent the breaking of the bridge at the tip of the river and the flooding of the slaughterhouse and the port in the hundred years flood in 2005.[44] The possibility of a 1000 years flood is contingent on the laws of nature and given the population density around the river and the inadequate preparation of the river canal to the average winter flow, the flood remains a potential disaster especially when added to the threat of an earthquake predicted within the next ten decades, as Lebanon stands on a fault.

Neither the catastrophic scenario, nor the terrible consequences of the over-urbanisation seem to prevent the remaining land from being exploited and developed in a speculative manner.

One question that arises is the interplay of private and public interests in the future of this area. The "Lebanese way" has almost always served and facilitated the interests of the private sector against the common public interest. Indeed when the French urbanist Michel Ecochard, upon request of the Lebanese government, proposed his urban plans in the 1940s-60s, which aimed at preserving large green areas, improving circulation and providing decent social housing for the poorest, little of his planning seems to have been implemented as nothing then stopped the interests of real estate developers of the private sector[45].

The industrial area of Jisr el Wati area around the river is today one of the few remaining underexploited spaces in Beirut. As stated earlier, it has recently attracted cultural practitioners such as Beirut Art Center, Ashkal Alwan Home Workspace and more recently The Station as well as Nabil Gholam's architectural firm. It witnesses now mushrooming construction sites which range from radical architectural projects for residential living such as Bernard khoury's Plot # 4371 (Artist Lofts) to massive skyscrapers designed by the architectural firm Erga, in which developers Achrafieh 4748 propose to create gated community complexes. The notion of gated community is not yet common in Beirut and could be questioned here as it could contribute to further emphasizing social inequalities and to separating coexisting communities.

The residential projects under construction are only one side of this gentrification, which involves also bigger and more ambitious development plans to rehabilitate the river. These proposed or speculated projects are born out of the pressure for urban land within Beirut and are motivated by a combination of ecological and welfare concerns but also by capitalist and commercial interests. There exist today a variety of projects centered around the Beirut river ranging from Beirut Green River (a project of at the initiative of the Lebanon's Green Party and envisioned by the architectural firm ERGA to transform 8.5km of the river through a "challenging development that will propagate environmentally sound practices while simultaneously redefining the real estate sector),[46] to urban projects such as Habib Debs' work within a master plan to create a "greennetwork" in the city by creating green paths around the river and connecting them to other public spaces,[47] Sandra Frem's stimulating work on "ecological continuity" of the river and the surrounding landscape in an environmentally friendly and socially responsible way, and the Beirut River Watershed Masterplan (a self-initiated project by theOtherDada (tOD), which "aims to promote the move from the existing deficient grey infrastructure to an environmentally friendly blue and green infrastructure,"[48] to students' projects for rehabilitating the river in university academic projects, and finally the Beirut Solar Snake project which is an initiative led by the Ministry of Energy and Water and the Lebanese Center for Energy Conservation to create a solar farm over the river.

The potential of the river and its surroundings for renewable and environmentally-safe energy (solar energy, water purification and redistribution), green public spaces and transportations, bike-paths and sports centers for people to enjoy, is promising for a balanced and organized development of an area long in neglect and its transformation into a source of energy, development and good living. In other words, the river's potential is re-locating the river at the center of Beirut in the current projects. The possibility of a better and greener living space is much needed today but perhaps the utopist and grandiose aspects of some projects is not merely driven by ecological ideas and civic responsibility as much as by the potential for benefits from the economical growth of this large area.

The future of the river is unknown, so is the coexistence of all the communities living in the area. What is known is the irreversible character of over-urbanisation around it, which could have been prevented with serious political action in dealing with urban planning and ecological matters that are crucial for our survival.

Today the river is dry most of the time and the border that was once defined is no longer a real border. The eastern limit of the city is indeterminate and keeps extending. Although this place is perceived as insalubrious, dirty and saturated with concrete, it inspires in me a certain melancholy and triggers many questions that stimulate my imagination.

Research assistant & contributor to the text: Sarah Sabban

Additional Research: Jessika Khazrik

About the artist

Born in Lebanon, Lamia Joreige is a visual artist and filmmaker who lives and works in Beirut. She uses archival documents and fictitious elements to reflect on the relation between individual stories and collective history. She explores the possibilities of representation of the Lebanese wars and their aftermath, and Beirut, a city at the centre of her imagery. Her work is essentially on time, the recordings of its trace and its effects on us.

Her works include, among many others, Under-Writing Beirut-Mathaf (mixed media installation, 2013); One Night of Sleep (Series of photograms 2013), Beirut, autopsy of a city (mixed media installation, 2010), Tyre 1,2,3,4,5, Portrait of a housing cooperative (video installation, 2010), 3 Triptychs (interactive installation, 2009), Full Moon (video, 2007), Nights and Days (video & series of prints, 2007).

She has presented her works in many exhibitions and international institutions including Sharjah Biennale, Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, Tate Modern, London, New Museum, New York and Modern Art Oxford.

Lamia Joreige is a co-founder and board member of Beirut Art Center, a non-profit space dedicated to contemporary art in Lebanon. She co-directed BAC from its opening in January 2009 until March 2014.